I have gathered them together here in one place to make it easier for people researching the Revo.

The thoughts and impressions in this blog are very much my own. I represent no individual or organisation.

Comments are disabled.

The time has come...

This is the post I never thought I'd write.

And yet ... I can't help wondering if it hasn't bee inevitable all along ...

As though everything that has come before has been building up to this moment.

Bear with me. Please. This is hard.

The time has come to put some flesh on those old bones.

I first went to Grenada in 1982, 3 years after the revolution.

I attended the anniversary celebrations.

My photo albums contain pictures of a smiling Maurice Bishop, PM of Grenada, embracing Samora Machel of Mozambique.

They're both dead now. History. I was there.

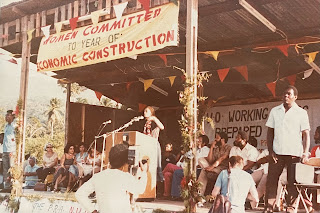

I was there too for the International Women's Day celebrations and heard Angela Davis speak.

Her photo's in my album too.

Angela Davis speaking at International Women's Day March 1982

That first month that I spent on this beautiful island in the company of its strong, proud, resilient people convinced me. Somehow ... in some way ... I knew that my own destiny was meshed with this beacon of hope in the Caribbean.

The coup was followed by 4 days of curfew. On 25th October, the US invaded. (Of necessity this is the most potted of accounts. You can see full details on this site if you're interested.) I stayed for as long as I could after the invasion, in spite of intense pressure to evacuate, but a few months later, penniless and heartbroken, I no longer had a choice. I returned to the UK to my frantic parents.

With hindsight, I recognise I was suffering from PTSD, but no one had heard of that condition back then. I think I was grieving. Even now, 25 years later, it's hard to describe the depth and intensity of the loss.

I returned the following year, but post-revo Grenada was a very different place and I couldn't see how to fit in or become a part of it. When I finally left in 1986, that should theoretically have been the end of my relationship with the island.

It wasn't though. The experience - seeing the hope and infinite possibility of the revo and then witnessing its destruction - had changed me forever.

Fast forward a couple of decades.

I'm an author with 5 books to my name. Friends often ask me why I don't ever write about what happened in Grenada.

'I sort of do,' I reply. 'Those experiences are part of me. They're part of my identity and so they inform everything I do and everything I write. It's just not explicit.'

Deep down though, I think I knew that this was only part of the truth and that one day I would have to bring the whole experience out of the shadows of my past and into my present.

I just couldn't see how.

A few months ago, I received an email from a guy in the US who had come across a photo on my website and wanted to know if I had any others.

I asked who he was and he told me he'd been part of the first wave of US soldiers in the invasion and wanted to see if he could recognise any of his old buddies in my photos. I politely informed him the images were not available.

The contact made me twitchy and a bit paranoid. I checked round the web and was shocked to see there's a big nostalgia trip in the US about the invasion. Grenada was a nice, short, simple war. And they won. Not like these nasty, messy, complicated wars they have nowadays in places like Afghanistan and Iraq, with their hideous resonances of the ultimate unwinnable war - Vietnam. I stumbled on a propaganda 'comic' telling the story of the brave US soldiers coming to the rescue of the grateful islanders, saving them from the red peril. The invasion took place a quarter of a century ago, yet I found forums where ex and current marines swapped stories and photos of the 'good old days in Grenada' when America could fight a war and win.

History. They were there and so was I. But my memories were very different from theirs.

More time passed. Then recently I 'met' Liane Spicer via the blogosphere. Liane lives in Trinidad and blogs at Wordtryst. We exchanged emails. I told her in about 4 lines about my involvement with Grenada. She said what other friends had already pointed out:

'What a fascinating story - your memoir will really be something! It's got all the elements: tropical island, politics, coup, invasion, romance, adventure, altruism... Are you writing it? Or maybe feeding it all into a novel?'

This was my reply:

'You know, I never have. When you put it like that, I suppose it does seem like it has literary potential. But…I don’t know. I’ve never figured out a way of doing it that I feel comfortable with. One day, maybe. As for feeding it in – well I suppose like everything else in life it has made me into what I am, so informs everything I do, but no direct feeding yet. Or maybe ever…'

(You want more spookiness? Having just gone back to this email exchange, I notice Liane's was sent on 25th October - 25 years to the day after the invasion.)

Grenada was back on my shoulder again. It wasn't going to go away.

Then I read a couple of reviews of Pynter Bender. The book is by a Grenadian author, Jacob Ross, and is set on the island. I bought the book and as I read I was overwhelmed by his evocation of the familiar sights and sounds. Memories came flooding back.

Grenada was whispering urgently in my ear.

So it was almost no surprise when I received an email from a woman who is making a documentary on the revo.

Faye-Anne Wilkinson was born in the UK. Her mother is Grenadian and Faye was a baby when the events I've been relating took place. The film is about her own personal search for truth and understanding. You can see the trailer for the film here.

History. I was there. And now I'm here, though I have no idea what will happen next. This post is the beginning of the next part of my journey.

Laying my cards on the table

I know I said I would plunge straight in, but I think you need a bit of my own back story first. A sort of 'laying my cards on the table', so you can have a picture of the young woman who arrived in Grenada in Feb 1982.So - who am I? That was a question I asked myself throughout my youth. It wasn't until I emerged from my turbulent teens, that I knew I wouldn't be fulfilling my parents' expectations. I was never going to marry young, to a nice Jewish boy, and bring up kids in a semi-detached within walking distance of where I'd grown up. (A bit more detail on my biog here.)

Once I'd worked out that this didn't mean I had some fundamental design fault,, I set about finding myself. And found 'me' in politics.

The 70s were my decade. While working in straight jobs, all my energy and enthusiasm went into changing the world. They were exciting times, when that felt like a genuine possibility. The revolution was always just around the corner. These were the pre-Thatcher days, before greed triumphed over altruism. I was active in all the radical movements of the time: the women's movement, anti-racism, Northern Ireland, anti-nuke, community politics...

Though many of the people I knew were members of the Socialist Workers' Party, or one of the myriad other left wing parties that abounded back then, I was never a 'joiner'. If anything, I was more radical, leaning to anarchy.

People associate anarchy with chaos and disorder, but when you think about it, a belief in anarchy as a workable alternative implies a fundamental belief in human nature: that, left to our own devices, human beings will choose to work together for the greater good. That we'll choose to access the capacity to do good that's within us all, rather than the potential for evil, greed and exploitation. It's not about every person for themselves, but about every person for every other.

Starry-eyed? Naive? Without a doubt, but it's still the way I feel deep inside. It's called hope.

So this was the young woman who decided in her mid-twenties that she needed to broaden her experiences and the best way to do that was to travel. To see other ways of living. To learn about other cultures, systems and attitudes. In 1980, I spent several months travelling across the US. The following year, I moved around, criss-crossing Europe. This last journey was undertaken with H, and it was at an open farm in Italy that we met J.

Travelling together by train when we left the farm, the three of us talked about possible destinations for a next trip. Grenada was mentioned in the list. I'd only vaguely heard of the island, and knew little other than that it was in the Caribbean and shouldn't be confused with Granada, in Spain.

Oh, and they'd had a revolution. Obvious choice.

Since this is a personal account as well as a historical and political one, there are some missing details in the previous posts that I've realised I need to fill in.

When I was back in London, somewhere between operations 2 and 3, I happened to overhear a conversation at a party in which Grenada was mentioned. I spoke to the woman afterwards and she told me her story, which bore a remarkable resemblance to that of mine and H.

C and her sister had visited Grenada on holiday and had the same emotional response as we had. Like us, they too planned to return but then her sister fell pregnant and C told me she was planning to go on her own. We promised to look out for each other.

H and I had been settled in Tempe for some time when C came to visit us. She was staying with a group of women in Carifta Cottages - a housing development on the south side of Grand Anse - but the others were due to leave shortly. C asked if we knew of anywhere she could rent. We asked round and found out that the little board house at the entrance to our gap was available.

C moved in and we became (and remain to this day) close friends. With a background in community development in the voluntary sector, she was working in Grenada as a volunteer with NACDA, the agency responsible for developing and encouraging co-operatives, the method that she had chosen to use her skills and experience to contribute to the Revo.

N was a local woman living with her children in Mt Parnassus who later moved further up the coast to Happy Hill. We became very close early on during our second stay and she devoured our collection of books with infectious enthusiasm, providing us with gratifying evidence of the need for the mobile library. In return, N taught us to cook and took us on day long trips into the country, from where we'd hitch back together, laden with sacks of fresh produce.

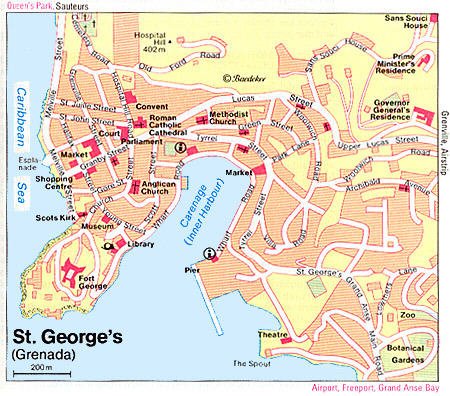

PC was a local mover and shaker in Tempe. An older man, he took it upon himself to act as our mentor. His street wisdom, connections and sheer good sense, as well as the respect people had for him proved invaluable for us. It was PC, for example, who took H and I into the ghetto - considered off limits to outsiders. The ghetto was a tiny warren of shacks just off the Carenage in St Georges. As soon as we walked in, our presence was challenged. PC only had to say that we were with him for the protests to cease.

It was strange; at first I would often be conscious of being the only white person in a particular place. I never felt vulnerable, but I certainly felt conspicuous. After a while though, as our faces became familiar and our presence drew less attention, I wouldn't even notice. Yet at the same time, it was vital to retain an awareness of who I was and where I came from. My story may have been running parallel to that of the people I met and became close to, but the truth is that I could never forget I was there by choice and not by birth or history.

Another regular visitor to our yard was R, a 10 year old diabetic boy who would come into our kitchen and cook up batches of plantain crisps. And then there was Y, who taught us belly dancing. And M, who'd had a scene with J but stayed on in our yard after she left. And...and... and...many more people who made up our daily landscape.

And then there was L. I have to talk about L.

Remember the background? When I returned to Grenada in June 1983, I had just come out of a disastrous 6 year relationship. I was determined to remain single, aware that I needed the space to sort my head out and work out how and why I had clung for so long to that particular shipwreck.

But remember too what I said about the tourist scene? A single woman was always going to be seen as available. As soon as we arrived, H resumed her previous relationship with B. No matter how much I protested that my single status was a choice and was not negotiable, I was under constant pressure from men wanting to be my 'personal friend'. I didn't kid myself that I was irresistibly gorgeous, knowing the lure was what I represented, not who I was personally.

One person stood out from the crowd who would approach me each time I went out and congregate at all hours of the day and night on our balcony. Not because he was any more persistent than the others, but because he was the only one who I felt made the effort to get to know the real me. I'd met L the previous year and had felt the connection then too, but had never acted on it. This time, L was determined to establish a relationship. I was equally determined to remain single.

I lasted two months. Two whole celibate singleton months, before embarking on the most tempestuous and passionate relationship I'd ever had. L of course had many years experience of being with women tourists. And I was certainly no blushing virgin.

Even so, I think it was clear to us both early on that what we had together was different from anything either of us had ever experienced before.

Some people suggested I start in the middle, others that I begin with a random image. The possibility of fictionalising my memories was mooted.

Some people suggested I start in the middle, others that I begin with a random image. The possibility of fictionalising my memories was mooted.

But the consensus is clear:

Just start writing.

So this is it.

Part 1 of The Revo Blog.

And it feels weighty with significance.

I've realised I need to give some background before I begin to tell what happened in that time when my own personal story became entwined with that of the island of Grenada.

This is not a diversion tactic, not is it control freakery.

I just don't want to keep interrupting the flow with distracting explanations once I begin.

So this post will operate as a kind of appendix. Scene setting, if you will.

Grenada - statistics

Area: 344 sq km (approx same size as London)

Population: approx 90,000 (less than the smallest London borough)

The people: 80% African, 3% East Indian, 10% mixed

Capital: St Georges

Principal exports: cocoa, bananas, spices

Grenada - a short history 1951-1983

1951 - Eric Gairy wins election

1962 - government dismissed for corruption

1972 - Gairy wins another election. JEWEL and MAP (see below) are formed

1973 - repression and unrest. JEWEL and MAP join to form NJM.

1974 - 3 month general strike. Rupert Bishop (father of Maurice) assassinated. Grenada achieves independence from Britain. NJM leadership arrested.

13 March 1979 - Revo! Gairy ousted in near bloodless coup

June 1980 - 3 women killed by bomb at rally

1982 - IMF congratulates PRG (see below) for economic performance. US becoming increasingly threatening and paranoid

(Feb-March 1982 - my first visit to Grenada)

1983 - Reagan refuses to meet delegation aimed at improving relations with US. Rifts appearing in NJM. Rumours and unrest.

19th October 1983 - coup

20th-23rd October 1983 - curfew

25th October 1983 - US invasion

(June 1983-February 1984 - my 2nd stay in Grenada)

(September 1985-March 1986 - my 3rd stay in Grenada)

Acronyms

Map - Movement for Assemblies of the People

JEWEL - Joint Endeavour for the Welfare, Education and Liberation of the People

NJM - New Jewel Movement

PRG - People's Revolutionary Government

PRA - People's Revolutionary Army

RFG - Radio Free Grenada

The people in Grenada's story

Eric Gairy - corrupt dictator ousted by revo

Maurice Bishop - charismatic Prime Minister and personification of the revo

Jacky Creft - Minister of Education. Maurice's partner. 5 months pregnant with his child at time of execution

The people in my story

Me - nice(ish) Jewish girl from London

H - the English woman I traveled with during my first 2 stays in Grenada

C - the English woman and close friend (still) who I met during my 2nd stay

J - the English woman and close friend (still) who was in Grenada June/July 2003. Mother of Gorgeous Goddaughter, born October 1986

L - my Grenadian partner

B - H's Grenadian partner

W - C's Grenadian partner

M - J's Grenadian partner. Father of Gorgeous Goddaughter

PC - local wheeler and dealer who acted as our mentor

In the next post, I will be starting at the beginning, explaining how I came to be in Grenada in the first place and sharing my experiences of the revo at a time when it was still filled with hope and potential. Over the following posts, I will be relating events as they occurred, using my diaries to ensure accuracy.

Writing this as fiction is impossible. For me, the whole point is that the truth should be known. The truth, unvarnished and unpalatable though it may be to some, as I saw it at the time.

I said in the comments on my previous post that I only cried once during my 4 hours with Faye, the film maker. That response crystallised everything for me. I remembered all over again the exact moment when the Grenadian revo, and with it my own world, fell apart. And I remembered also how crucial it had seemed to me at the time to ensure people understood. I felt this huge weight of responsibility and it's never been discharged.

As the years passed, it was clear that the defining event that most people associated with Grenada was the invasion. Not the revo. And not the coup. I too succumbed in the end. US Imperialism was an easy enemy to focus on. War is something people think they're able to wrap their minds around. And traumatic though the invasion had been, it became less painful for me to reflect on than the events that preceded it.

Over time, my experiences coalesced into a series of well-worn, neatly-packaged anecdotes. Gone were the days when I had first returned to London in 1984, when people would go to great lengths to avoid my Ancient Mariner-esque intensity, determined to force them to see what I had seen and learn what I had learned.

Well, those days are back. The posts that follow comprise a true and full record at last. Being a blog, people can choose whether to read or ignore, without me having to deal with the angst.

But the words will be out there. Accessible to all. At last.

Though many of the people I knew were members of the Socialist Workers' Party, or one of the myriad other left wing parties that abounded back then, I was never a 'joiner'. If anything, I was more radical, leaning to anarchy.

People associate anarchy with chaos and disorder, but when you think about it, a belief in anarchy as a workable alternative implies a fundamental belief in human nature: that, left to our own devices, human beings will choose to work together for the greater good. That we'll choose to access the capacity to do good that's within us all, rather than the potential for evil, greed and exploitation. It's not about every person for themselves, but about every person for every other.

Starry-eyed? Naive? Without a doubt, but it's still the way I feel deep inside. It's called hope.

So this was the young woman who decided in her mid-twenties that she needed to broaden her experiences and the best way to do that was to travel. To see other ways of living. To learn about other cultures, systems and attitudes. In 1980, I spent several months travelling across the US. The following year, I moved around, criss-crossing Europe. This last journey was undertaken with H, and it was at an open farm in Italy that we met J.

Travelling together by train when we left the farm, the three of us talked about possible destinations for a next trip. Grenada was mentioned in the list. I'd only vaguely heard of the island, and knew little other than that it was in the Caribbean and shouldn't be confused with Granada, in Spain.

Oh, and they'd had a revolution. Obvious choice.

Relationships

Since this is a personal account as well as a historical and political one, there are some missing details in the previous posts that I've realised I need to fill in.

When I was back in London, somewhere between operations 2 and 3, I happened to overhear a conversation at a party in which Grenada was mentioned. I spoke to the woman afterwards and she told me her story, which bore a remarkable resemblance to that of mine and H.

C and her sister had visited Grenada on holiday and had the same emotional response as we had. Like us, they too planned to return but then her sister fell pregnant and C told me she was planning to go on her own. We promised to look out for each other.

H and I had been settled in Tempe for some time when C came to visit us. She was staying with a group of women in Carifta Cottages - a housing development on the south side of Grand Anse - but the others were due to leave shortly. C asked if we knew of anywhere she could rent. We asked round and found out that the little board house at the entrance to our gap was available.

C moved in and we became (and remain to this day) close friends. With a background in community development in the voluntary sector, she was working in Grenada as a volunteer with NACDA, the agency responsible for developing and encouraging co-operatives, the method that she had chosen to use her skills and experience to contribute to the Revo.

N was a local woman living with her children in Mt Parnassus who later moved further up the coast to Happy Hill. We became very close early on during our second stay and she devoured our collection of books with infectious enthusiasm, providing us with gratifying evidence of the need for the mobile library. In return, N taught us to cook and took us on day long trips into the country, from where we'd hitch back together, laden with sacks of fresh produce.

PC was a local mover and shaker in Tempe. An older man, he took it upon himself to act as our mentor. His street wisdom, connections and sheer good sense, as well as the respect people had for him proved invaluable for us. It was PC, for example, who took H and I into the ghetto - considered off limits to outsiders. The ghetto was a tiny warren of shacks just off the Carenage in St Georges. As soon as we walked in, our presence was challenged. PC only had to say that we were with him for the protests to cease.

It was strange; at first I would often be conscious of being the only white person in a particular place. I never felt vulnerable, but I certainly felt conspicuous. After a while though, as our faces became familiar and our presence drew less attention, I wouldn't even notice. Yet at the same time, it was vital to retain an awareness of who I was and where I came from. My story may have been running parallel to that of the people I met and became close to, but the truth is that I could never forget I was there by choice and not by birth or history.

Another regular visitor to our yard was R, a 10 year old diabetic boy who would come into our kitchen and cook up batches of plantain crisps. And then there was Y, who taught us belly dancing. And M, who'd had a scene with J but stayed on in our yard after she left. And...and... and...many more people who made up our daily landscape.

And then there was L. I have to talk about L.

Remember the background? When I returned to Grenada in June 1983, I had just come out of a disastrous 6 year relationship. I was determined to remain single, aware that I needed the space to sort my head out and work out how and why I had clung for so long to that particular shipwreck.

But remember too what I said about the tourist scene? A single woman was always going to be seen as available. As soon as we arrived, H resumed her previous relationship with B. No matter how much I protested that my single status was a choice and was not negotiable, I was under constant pressure from men wanting to be my 'personal friend'. I didn't kid myself that I was irresistibly gorgeous, knowing the lure was what I represented, not who I was personally.

One person stood out from the crowd who would approach me each time I went out and congregate at all hours of the day and night on our balcony. Not because he was any more persistent than the others, but because he was the only one who I felt made the effort to get to know the real me. I'd met L the previous year and had felt the connection then too, but had never acted on it. This time, L was determined to establish a relationship. I was equally determined to remain single.

I lasted two months. Two whole celibate singleton months, before embarking on the most tempestuous and passionate relationship I'd ever had. L of course had many years experience of being with women tourists. And I was certainly no blushing virgin.

Even so, I think it was clear to us both early on that what we had together was different from anything either of us had ever experienced before.

Why Revo

A couple of friends whose opinions I trust have told me they're concerned that my use of the abbreviation 'Revo' might be sending out the wrong signals. Since I'm very anxious this should not be the case, I thought I should explain.

While in official circles and on printed information the period was always referred to in Grenada as 'the revolution', on the streets and in conversation it was colloquially referred to as 'the Revo'. For me, this implied affection and ownership: there had been other revolutions in other places, but what was happening in Grenada was unique. It belonged to them. It was their Revo.

For this reason I chose to use the abbreviation in these posts. I would be appalled to think that anyone who didn't know the context, might think that my decision to refer in that way to what happened between 13 March 1979 and 19 October 1983 implied I was trivialising or belittling the Grenadian revolution.

I hope that it is clear to anyone and everyone reading this series of posts that my respect, admiration and genuine awe for what the Grenadian people achieved in that time against all the odds know no bounds.

I was - and still am - humbled by what I witnessed.

While in official circles and on printed information the period was always referred to in Grenada as 'the revolution', on the streets and in conversation it was colloquially referred to as 'the Revo'. For me, this implied affection and ownership: there had been other revolutions in other places, but what was happening in Grenada was unique. It belonged to them. It was their Revo.

For this reason I chose to use the abbreviation in these posts. I would be appalled to think that anyone who didn't know the context, might think that my decision to refer in that way to what happened between 13 March 1979 and 19 October 1983 implied I was trivialising or belittling the Grenadian revolution.

I hope that it is clear to anyone and everyone reading this series of posts that my respect, admiration and genuine awe for what the Grenadian people achieved in that time against all the odds know no bounds.

I was - and still am - humbled by what I witnessed.

Just start writing

Some people suggested I start in the middle, others that I begin with a random image. The possibility of fictionalising my memories was mooted.

Some people suggested I start in the middle, others that I begin with a random image. The possibility of fictionalising my memories was mooted.But the consensus is clear:

Just start writing.

So this is it.

Part 1 of The Revo Blog.

And it feels weighty with significance.

I've realised I need to give some background before I begin to tell what happened in that time when my own personal story became entwined with that of the island of Grenada.

This is not a diversion tactic, not is it control freakery.

I just don't want to keep interrupting the flow with distracting explanations once I begin.

So this post will operate as a kind of appendix. Scene setting, if you will.

Grenada - statistics

Area: 344 sq km (approx same size as London)

Population: approx 90,000 (less than the smallest London borough)

The people: 80% African, 3% East Indian, 10% mixed

Capital: St Georges

Principal exports: cocoa, bananas, spices

Grenada - a short history 1951-1983

1951 - Eric Gairy wins election

1962 - government dismissed for corruption

1972 - Gairy wins another election. JEWEL and MAP (see below) are formed

1973 - repression and unrest. JEWEL and MAP join to form NJM.

1974 - 3 month general strike. Rupert Bishop (father of Maurice) assassinated. Grenada achieves independence from Britain. NJM leadership arrested.

13 March 1979 - Revo! Gairy ousted in near bloodless coup

June 1980 - 3 women killed by bomb at rally

1982 - IMF congratulates PRG (see below) for economic performance. US becoming increasingly threatening and paranoid

(Feb-March 1982 - my first visit to Grenada)

1983 - Reagan refuses to meet delegation aimed at improving relations with US. Rifts appearing in NJM. Rumours and unrest.

19th October 1983 - coup

20th-23rd October 1983 - curfew

25th October 1983 - US invasion

(June 1983-February 1984 - my 2nd stay in Grenada)

(September 1985-March 1986 - my 3rd stay in Grenada)

Acronyms

Map - Movement for Assemblies of the People

JEWEL - Joint Endeavour for the Welfare, Education and Liberation of the People

NJM - New Jewel Movement

PRG - People's Revolutionary Government

PRA - People's Revolutionary Army

RFG - Radio Free Grenada

The people in Grenada's story

Eric Gairy - corrupt dictator ousted by revo

Maurice Bishop - charismatic Prime Minister and personification of the revo

Bernard Coard - deputy PM. Widely perceived as the leader and would-be beneficiary of the coup (though he has consistently denied this)

Hudson Austin - head of the PRA and 'voice' of the coupJacky Creft - Minister of Education. Maurice's partner. 5 months pregnant with his child at time of execution

The people in my story

Me - nice(ish) Jewish girl from London

H - the English woman I traveled with during my first 2 stays in Grenada

C - the English woman and close friend (still) who I met during my 2nd stay

J - the English woman and close friend (still) who was in Grenada June/July 2003. Mother of Gorgeous Goddaughter, born October 1986

L - my Grenadian partner

B - H's Grenadian partner

W - C's Grenadian partner

M - J's Grenadian partner. Father of Gorgeous Goddaughter

PC - local wheeler and dealer who acted as our mentor

In the next post, I will be starting at the beginning, explaining how I came to be in Grenada in the first place and sharing my experiences of the revo at a time when it was still filled with hope and potential. Over the following posts, I will be relating events as they occurred, using my diaries to ensure accuracy.

Writing this as fiction is impossible. For me, the whole point is that the truth should be known. The truth, unvarnished and unpalatable though it may be to some, as I saw it at the time.

I said in the comments on my previous post that I only cried once during my 4 hours with Faye, the film maker. That response crystallised everything for me. I remembered all over again the exact moment when the Grenadian revo, and with it my own world, fell apart. And I remembered also how crucial it had seemed to me at the time to ensure people understood. I felt this huge weight of responsibility and it's never been discharged.

As the years passed, it was clear that the defining event that most people associated with Grenada was the invasion. Not the revo. And not the coup. I too succumbed in the end. US Imperialism was an easy enemy to focus on. War is something people think they're able to wrap their minds around. And traumatic though the invasion had been, it became less painful for me to reflect on than the events that preceded it.

Over time, my experiences coalesced into a series of well-worn, neatly-packaged anecdotes. Gone were the days when I had first returned to London in 1984, when people would go to great lengths to avoid my Ancient Mariner-esque intensity, determined to force them to see what I had seen and learn what I had learned.

Well, those days are back. The posts that follow comprise a true and full record at last. Being a blog, people can choose whether to read or ignore, without me having to deal with the angst.

But the words will be out there. Accessible to all. At last.

.jpg)